“No motion of the civil battle has been so little understood as that of Seven Pines,” Accomplice Common Joseph E. Johnston would write in his 1874 memoir, Narrative of Army Operations. Ironic, as Johnston’s personal actions throughout and after the essential Peninsula Marketing campaign battle on Could 31–June 1, 1862, are actually a motive why that is so.

Captain George W. Mindil of the 61st Pennsylvania Infantry, a employees officer within the Union Military of the Potomac that confronted Johnston’s Military of Northern Virginia through the battle, later noticed that the enemy commander’s “plan was faultless….[H]advert this plan been totally executed…the left wing of McClellan’s military would have sustained irreparable catastrophe and the retreat of the entire [Union] military would have adopted.”

As an alternative, the end result of the two-day conflict that resulted in additional than 11,000 casualties (usually identified to Northerners as Honest Oaks) was inconclusive. As well as, controversy and acrimony arose when each Johnston and one among his prime subordinates, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, audaciously asserted that regardless of a easy “misunderstanding” between the 2, victory nonetheless would have been doable had it not been for the “incompetence” of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger, a division commander in Longstreet’s Proper Wing.

The phrase “misunderstanding” usually implies the fee of an sincere mistake or maybe a communication failure—often indicating no ill-intent by the members. The purported miscue at Seven Pines, nevertheless, was a well-crafted fabrication designed each to defend Longstreet’s poor decision-making and insubordinate conduct through the battle and to deflect consideration away from Johnston’s personal management failures.

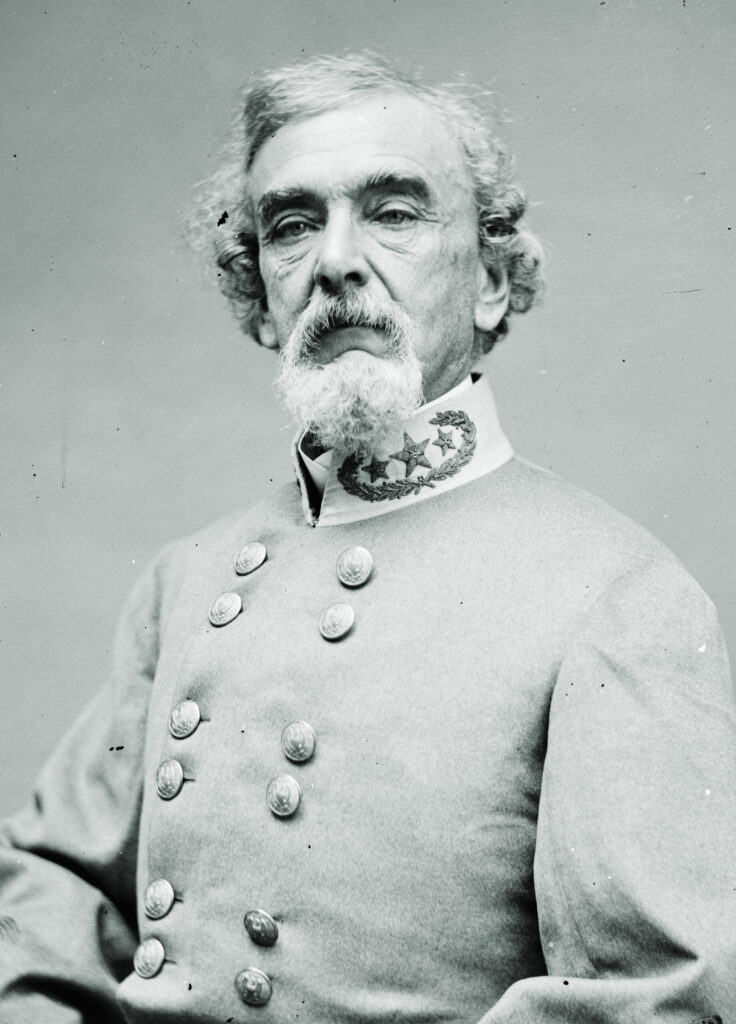

As Colonel Charles Marshall, Accomplice Common Robert E. Lee’s aide-de-camp, would caustically level out, Johnston had the knack of compensating for his deficiencies by his use of the “sure ‘agility’ of rationalization.” Concerning Johnston’s put up–Seven Pines account, Marshall wrote that “a lie effectively adhered to & typically repeated, will typically serve a person’s goal in addition to the reality & higher.”

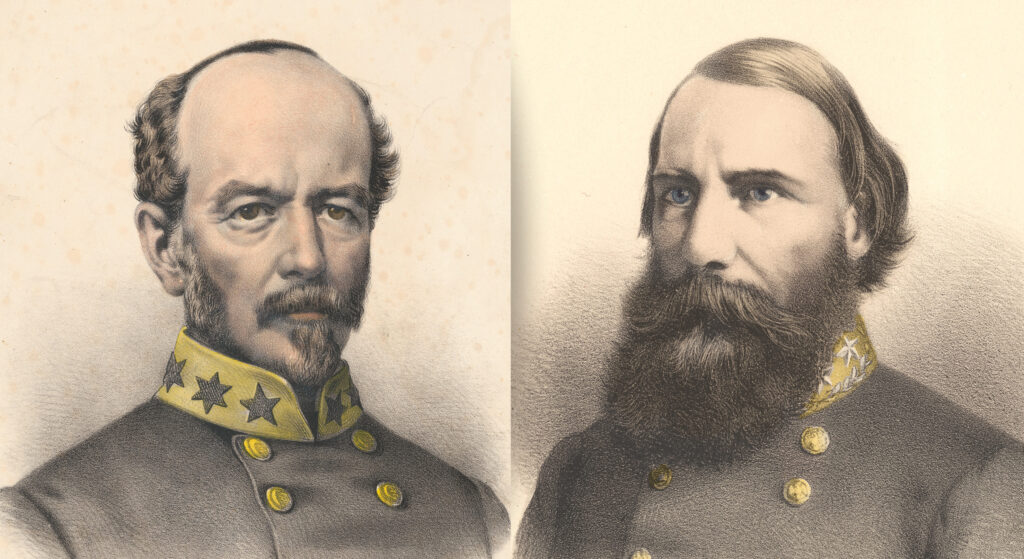

(Nationwide Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Establishment)

By late Could 1862, Johnston’s relationship with Accomplice President Jefferson Davis was so strained, had he acknowledged the reality concerning the battle, it might have tarnished each his and Longstreet’s reputations. That left the unlucky Huger because the goal of an unconscionable assault.

“Misunderstanding” first appeared in Johnston’s June 28, 1862, letter to Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith, his Left Wing commander, in response to Smith’s after-action report. “My Expensive Gustavus,” Johnston wrote, “I inclose herewith the primary three sheets of your report, to ask a modification, or omission reasonably. They comprise two topics which I meant by no means to make usually identified. I consult with the misunderstanding [italics added by author] between Longstreet and myself in regard to the route of his division.”

The connection between Johnston and Smith had as soon as been shut. In August 1861, in reality, Johnston wrote to Davis that “Smith is an officer of excessive potential, match to command in chief.” And the next February, Johnston knowledgeable Davis: “I regard Maj. Gen. G.W. Smith as completely essential to this military.”

Johnston’s heat tone now belied their latest pressure. Along with sustaining the alleged misunderstanding, Johnston justified his request to omit parts of Smith’s report as “these issues concern Longstreet and myself alone. I’ve no hesitation in asking you to strike them out of your report as they in no method concern your operations.”

Though Smith complied with Johnston’s request “due to [his] nice private attachment” to his commander, he maintained a duplicate of his unique and entered a be aware stating that Johnston “is mistaken in supposing that the misunderstanding between himself and Common Longstreet didn’t have an effect on the operations of my division.”

The suppression of Smith’s report would change into the cornerstone of the burgeoning “misunderstanding” fantasy. Smith, nevertheless, correctly saved copies of all his communications. In 1884, he printed his unique report together with these beforehand omitted references.

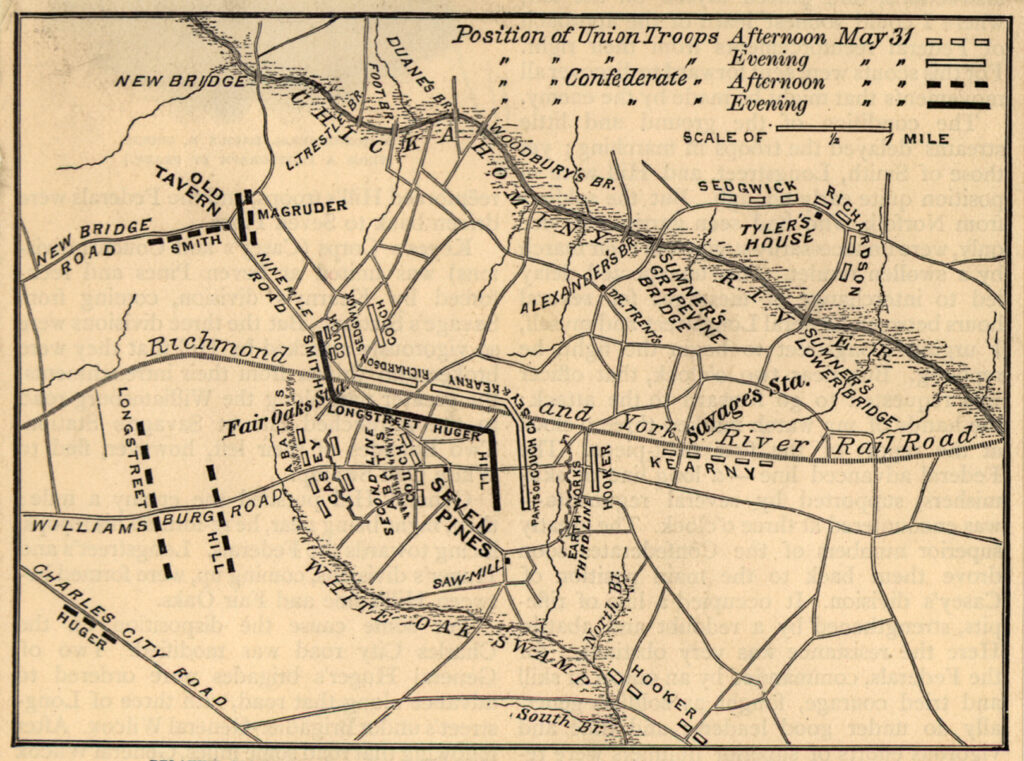

Plan of Assault

Seven Pines/Honest Oaks can be a definitive battle in Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s ill-fated Peninsula Marketing campaign. On Could 20, “Little Mac” had begun shifting a part of his military throughout the Chickahominy River, closing to inside 10 miles of Richmond. The 12,500-man 4th Corps, below Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes, crossed the river close to Backside’s Bridge, adopted by Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman’s third Corps. Keyes would transfer his corps to Seven Pines; Heintzelman’s corps, with 15,000 males, remained close to the Chickahominy—the 2 models largely deployed alongside the Williamsburg Street. Though White Oak Swamp supplied safety to their left, their proper flank was weak, missing a pure barrier.

Seven Pines lay roughly six miles east of Richmond on the intersection of the Williamsburg and 9 Mile roads. Roughly one mile north of Seven Pines, alongside 9 Mile Street and the Richmond & York River Railroad, sat a small depot referred to as Honest Oaks Station. To guard his proper flank, Keyes positioned a brigade on the depot.

The Accomplice strains started at some extent two miles north of the station alongside 9 Mile Street close to an space often known as Outdated Tavern. There have been roughly 87,800 males in Johnston’s military, extending in an arc alongside the Chickahominy to the north all the way down to Drewry’s Bluff.

Johnston totally acknowledged the vulnerability of the Federal place south of the Chickahominy; nevertheless, he additionally had realized that Brig. Gen. Irwin McDowell’s 1st Corps had left Fredericksburg, heading towards McClellan’s foremost strains. A strike on McClellan above the Chickahominy was important earlier than that would occur.

Throughout a council of battle on Could 28, Johnston proposed an assault on the Union place at Mechanicsville, which might forestall McDowell from linking with Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s fifth Corps. After they realized McDowell’s corps had begun returning to Fredericksburg, Smith advocated calling off the assault. Johnston at first agreed, which infuriated Longstreet, nonetheless satisfied a turning motion towards the Federal place would yield sure victory. Johnston was swayed by his subordinate’s ardour.

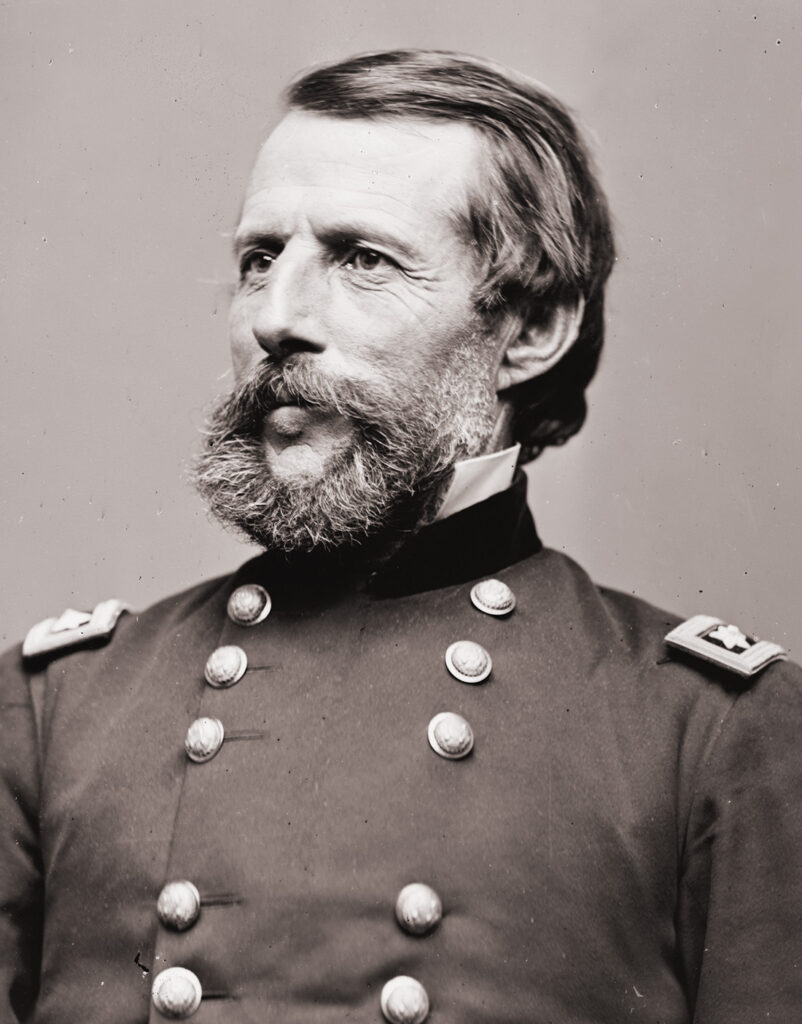

Massachusetts native, commanded the 12,500-man Union 4th Corps in

the battle. His efforts, significantly within the first day’s preventing, earned him a brevet brigadier basic’s promotion.

(Library of Congress)

On Could 30, Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill in Longstreet’s Proper Wing reported that Keyes’ corps was arrayed in pressure alongside the Williamsburg Street however was weak from the Charles Metropolis Street. Johnston promptly ordered an assault to happen the next day.

With out Smith in attendance, Johnston met with Longstreet the afternoon of Could 30. After designating Longstreet because the commander of the assaulting pressure, consisting of three divisions, the generals weighed their choices on how one can finest conduct the assault. They decided that at 8 a.m. Hill’s command would open the assault alongside the Williamsburg Street, hanging the 4th Corps on its entrance.

Hill’s advance, nevertheless, required the inclusion of the two,200-man brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes, presently posted alongside the Charles Metropolis Street. To deal with that want, Johnston ordered Huger, in Longstreet’s Wing, to march his 6,250-man division over from Drewry’s Bluff to alleviate Rodes’ Brigade previous to the assault. Huger would then occupy a place reverse the 4th Corps’ left flank.

Longstreet would then transfer his 13,800-man division, commanded right here by Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, east alongside the 9 Mile Street to Outdated Tavern, placing it squarely on Keyes’ proper flank.

One concern the generals had with this plan was how one can bolster the general power of Hill’s attacking pressure. Johnston may transfer Longstreet’s Division (below Anderson) to help Hill, however sophisticated logistical components dominated out that possibility. Not solely would Anderson’s males have to maneuver through the evening, it might additionally necessitate coordination with Huger’s command, as every division can be required to occupy the identical stretch of the Williamsburg Street, even when solely quickly.

Another choice in supporting Hill was to reposition Gustavas Smith’s six-brigade division (with Brig. Gen. William H.C. Whiting in command). This appeared as essentially the most logical alternative, but it surely additionally posed an unavoidable complication. As a result of Smith outranked Longstreet, the motion would place Smith accountable for the assault and never “Outdated Pete.” As Johnston had designated Longstreet as the general commander of offensive operations, he determined towards that possibility, selecting as a substitute to advance Smith’s Division nearer to Outdated Tavern in help of Longstreet. After contemplating his choices, and with an intense rainstorm now unloading on the realm, Johnston decided that reasonably than transfer Longstreet or any extra pressure to the Williamsburg Street, the assault would proceed as adopted:

1) Earlier than daybreak, Common Huger would proceed to the Charles Metropolis Street and relieve Rodes’ Brigade, enabling Rodes to affix Hill.

2) With Rodes’ arrival, Hill would launch the assault alongside the Williamsburg Street.

3) Doing so can be the sign for Longstreet’s flank assault down the 9 Mile Street.

4) Smith’s Division would stay in reserve alongside the 9 Mile Street in help of Longstreet.

“There was…no motive why the orders for march ought to be misconstrued or misapplied,” Longstreet later wrote. “I used to be with Common Johnston the entire time that he was engaged in planning and ordering the battle, heard each phrase and thought expressed by him of it, and acquired his verbal orders; Generals Huger and Smith acquired his written orders.”

Apparently, Longstreet by no means recognized or described in his report or postwar writing the precise orders he had acquired. Nor did Longstreet reveal his division’s personal marching orders—though he did present particulars of these he had issued Huger, Smith, and McLaws. Moreover, Longstreet by no means divulged the following orders he issued to his division, or to Hill.

(Library of Congress)

What, due to this fact, went flawed? Merely put, Longstreet went rogue. No matter his full data of Johnston’s intentions, he willingly altered the assault plans. No “sincere mistake” or “failure to grasp instructions appropriately” was concerned:

1) Longstreet not solely disregarded Johnston’s unique order, he by no means communicated to his commander his actions, location, standing, or progress as soon as the assault started.

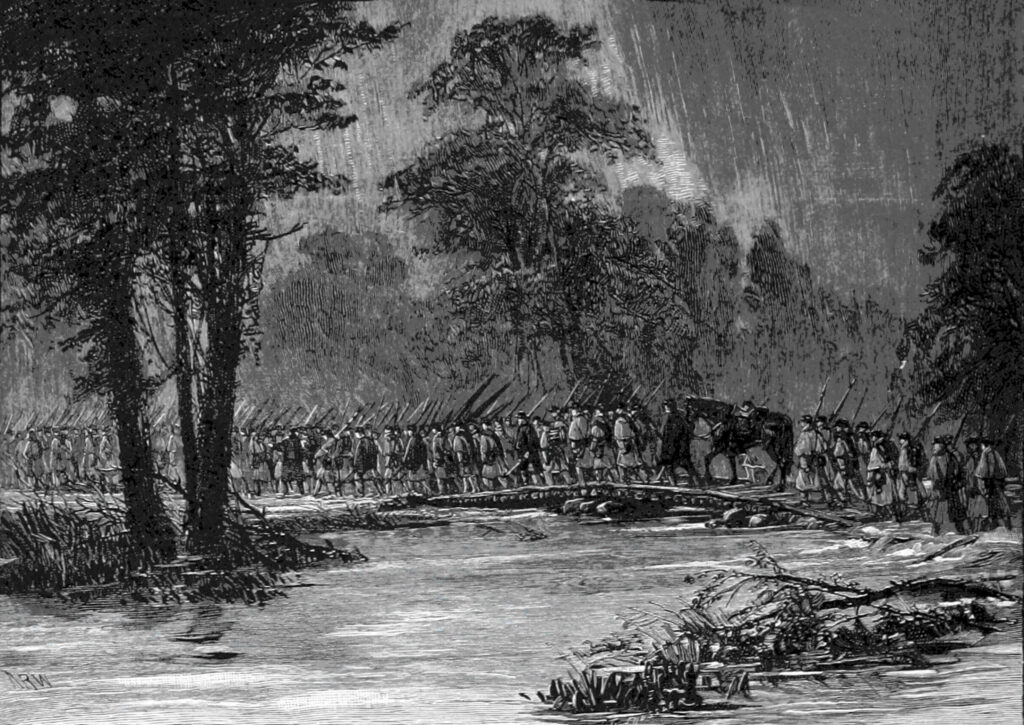

2) He someway additionally ignored the climate, which he totally knew was dreadful, later writing, “Whereas but affairs have been into account [on May 30], a terrific storm of vivid lightning, thunderbolts, and rain, as extreme as ever identified to any local weather, burst upon us, and continued by the evening kind of extreme. Within the first lull I rode from Common Johnston’s to my head-quarters, and despatched orders for [an] early march.”

3) He ignored the significance of Huger’s orders to alleviate Rodes on the Charles Metropolis Street.

As a result of Johnston and Longstreet conferred for a while, it’s laborious to imagine Longstreet was not knowledgeable which street he was to make use of. Longstreet, in fact, had lengthy been hoping for an impartial command. Selecting to comply with the Williamsburg Street was clearly a chance for him to flout his orders for an assault plan of his personal discretion.

All six of Longstreet’s brigades have been positioned close to the 9 Mile Street, which required solely a brief march east to succeed in Outdated Tavern. Had Longstreet’s brigades moved out at 3:30 a.m., they might have reached Outdated Tavern by 6 a.m.

“The tactical dealing with of the battle on the Williamsburg Street was left to my care, in addition to the overall conduct of affairs south of the York River Railroad,” Longstreet later wrote, however he by no means supplied to clarify why he altered Johnston’s plan and even why he didn’t talk along with his commander till late within the afternoon—undeniably insubordinate conduct.

As for the climate’s influence, Longstreet had held area instructions from First Manassas by the Peninsula Marketing campaign. His expertise was in depth sufficient to comprehend a “terrific” and “extreme” rainstorm would severely hamper the nighttime motion of a 13,800-man division. Had Longstreet adopted orders and marched east alongside the 9 Mile Street, crossing the flooded Gillies Creek wouldn’t have been the roadblock it was.

A Disputed Crossing

The motion of Huger’s Division was the important thing to a profitable assault. In relieving Rodes alongside the Charles Metropolis Street, Rodes may be part of Hill as ordered and the assault on Keyes’ place launched. However when the lead components of Longstreet’s Division descended the steep bluffs towards Gillies Creek, they discovered it “financial institution full” and unfordable. To cross the swollen creek, Longstreet’s males positioned a wagon within the stream as a trestle and laid planks to each banks, permitting a single-file crossing.

As that started, nevertheless, Huger appeared. Regardless of understanding what was at stake, Longstreet responded that “[a]s we have been earlier on the creek, it gave us priority over Huger’s division…” Hill’s assault must wait.

It’s also mystifying that Longstreet later insisted he believed Huger had already crossed Gillies Creek. Little doubt a division the dimensions of Huger’s actually would have left proof of such a crossing.

Discovering Longstreet already occupying the creek was simply one among a day stuffed with surprises for Huger, who additionally revealed it was “the primary I knew” of a deliberate Could 31 assault. Even when one accepts Longstreet’s “misunderstanding” of his orders, it doesn’t justify his rationale in stopping Huger’s Division from advancing to its assigned Charles Metropolis Street place.

(CBW (Alamy Inventory Photograph))

Johnston’s duty for the assault’s implosion can’t be ignored both. In any case, Huger acquired solely two communications from him: one at 8:40 p.m. Could 30; the opposite Could 31, with no time indicated. Johnston was directing Huger to alleviate Rodes, and that “when you discover no robust physique in your entrance, will probably be effectively to help Common Hill.”

Huger interpreted that to imply he was shifting to a brand new place and never into battle, as the one basic named in both be aware was Hill. Neither talked about Longstreet being accountable for the wing, Hill’s anticipated assault, nor Huger’s position in that assault. He additionally described the communications from Johnston as being an “autograph be aware and never an official order.”

The shortage of readability relating to Huger’s anticipated position within the upcoming battle is borne out in his assertion, “If I’d have been notified that Longstreet was to move, I’d have made one other crossing.” When he met with Longstreet at Hill’s headquarters, Huger additionally totally realized: “He was shifting to assault the enemy.”

Longstreet Crafts a Narrative

The one basic who deserves absolution for the opening assault’s delay is Huger. By June 7, Longstreet had already put the “misunderstanding” fantasy and the character assassination of Huger in his letter to Johnston. The letter started pleasant sufficient, with Longstreet expressing syrupy concern for the significantly wounded commander earlier than segueing into claims that, regardless of his division’s heroics, he had been victimized by Huger’s lethargy:

“The failure of full success [May 31] I attribute to the sluggish actions of Common Huger’s command….I can’t however assist assume that the show of his forces on the left flank of the enemy…would have accomplished the affair.”

Longstreet asserted deceitfully that Huger’s ineffectiveness “threw maybe the toughest a part of the battle upon my very own poor division. It’s tremendously lower up….Our ammunition was almost exhausted when [General] Whiting moved.” “Altogether,” he concluded, “it was very effectively, however I can’t assist however remorse it was not full.”

Mississippi Division, relegated to ordnance administrative duties.

(Library of Congress)

On the battle’s first day, nevertheless, Longstreet had used solely six of the 13 brigades out there to him. 4 of these belonged to Hill, with “Pete” sending solely two extra ahead—these of Colonels James Kemper and Micah Jenkins—each at Hill’s request for extra help. Of the 13,800 males he had current for obligation in his division, almost 9,500 of them by no means fired a shot.

Information don’t help Longstreet’s declare his division was “tremendously lower up” and its “ammunition almost exhausted.” Kemper’s and Jenkins’ losses have been solely 7 % of the division’s total casualties. In contrast, Hill engaged his whole 10,250-man division and reported almost 3,000 casualties (29 %). In preventing later that afternoon, Whiting (dealing with Smith’s Division) suffered 1,278 casualties (13.7 % of the ten,590 males current).

The aim of Longstreet’s letter to Johnston was twofold. First, it launched the narrative that every one blame was to be squarely positioned on Huger. Second, it signaled a measure Johnston may use in explaining why full victory had not been not achieved, which might be significantly helpful when supplied to a more and more essential President Davis and the Richmond press.

In his after-action report, ready three days later, Longstreet asserted, “Agreeably to verbal directions from the commanding basic,” which signifies to an uninformed reader that what adopted was in accordance with Johnston’s directive. Any “misunderstanding” of verbal directions may thus be seen as a helpful alibi as a substitute of an admission of willful insubordination.

“The division of Maj. Gen. Huger was meant to make a robust flank motion across the left of the enemy’s place and assault him within the rear of that flank….,” Longstreet famous. “[T]his division didn’t get into place in time for any such assault.”

His brazen distortion of information didn’t finish there: “I’ve motive to imagine that the affair would have been a whole success had the troops upon the precise been put in place inside eight hours of the right time.” Longstreet adopted with: “Among the brigades of Common Huger’s division took half in defending our place on Sunday [June 1], however…didn’t present the identical steadiness and dedication of Hill’s division and my very own.”

This report, and Longstreet’s letter written June 7, put Johnston in an ungainly place, as he was now compelled to help this narrative reasonably than provide a extra correct and truthful account.

Solely three of six brigade commanders in Anderson’s ranks issued after-action studies—Colonel Micah Jenkins, Brig. Gen. George Pickett, and Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox—and no officers within the unit’s 23 regiments did so. Plus, the three brigades with no studies issued weren’t engaged on Could 31, and solely minimally engaged on June 1, with no reported casualties.

Jenkins’ report detailed the in depth preventing by his portion of Anderson’s Brigade, however just for Could 31, and Anderson didn’t full a report. Pickett’s report was minimalist at finest, with no perception on his preliminary marching orders or to any subsequent orders from Longstreet earlier than 9 p.m. Could 30.

Solely Wilcox talked about any substantive content material of Longstreet’s orders: “On the thirtieth ultimo[,] orders have been acquired to be ready with ammunition….for an early march the next morning. At 6:30 a.m. the brigade moved from its camp close to the Mechanicsville Pike by by-paths throughout to the junction of the Charles Metropolis and Williamsburg Roads” [italics added by author].

Wilcox’s report clearly signifies no orders involving motion towards Outdated Tavern on the 9 Mile Street, as would have been Johnston’s expectation. One can presume that every of these in brigade command acquired related orders, as the entire division wound up alongside the Williamsburg Street.

The orders described in Wilcox’s report would have been issued shortly after Longstreet left Johnston’s headquarters at roughly 9 p.m. Could 30. In 1896, Longstreet wrote: “There was no motive why the orders for march ought to be misconstrued or misapplied”—a curious remark contemplating Longstreet’s June 10, 1862, report, which didn’t disclose the character of his orders. It’s fascinating how Longstreet maintained there was “no motive” for misconstruing his orders, but his report focuses on Hill and Huger whereas providing little knowledge relating to his personal division’s actions.

A standard perception supplied on Longstreet’s behalf is the shortage of readability of Johnston’s verbal orders. Johnston, nevertheless, clearly meant and anticipated Longstreet to function as a commander of three divisions and to interact his division from Outdated Tavern upon listening to the opening of Hill’s assault. Longstreet did not do both. Even when one accepts a “misunderstanding,” Longstreet’s battlefield conduct is difficult to justify.

In 1877, Longstreet finest described his lack of management when he wrote to Hill: “I don’t bear in mind giving an order on that area aside from to ship you my brigades as you referred to as for them.” Hill later wrote that “Longstreet was not on the sphere in any respect on the thirty first of Could, and didn’t see any of the preventing.” And Longstreet’s poor battlefield management continued June 1, with Hill recalling he “acquired no orders from Common Longstreet no matter.” Longstreet’s admission and Hill’s verifications actually don’t painting the actions of a wing commander chargeable for actively directing and managing the operations of three divisions.

False Statements

By putting his affinity for Longstreet above the reality, Johnston shared equally in crafting the “misunderstanding” and in actively partaking within the character assassination of Huger.

After graduating from West Level in 1825, Benjamin Huger spent the subsequent 35 years primarily as an ordnance officer within the U.S. Military. In 1861, he resigned from Federal service to affix the Accomplice Military however rapidly ran afoul of an investigation carried out by the Accomplice Home of Representatives for failure to bolster and provide troops at Roanoke Island, N.C., the place he commanded. His fame sullied, Huger turned a straightforward goal for additional criticism, whether or not warranted or not.

Neither Johnston nor Longstreet revered Huger, and Johnston had publicly criticized Huger for abandoning the Norfolk Naval Yards in Could 1862 and the following demolition of the ironclad CSS Virginia, though Huger had merely been following Johnston’s personal orders.

Though Huger lacked expertise as a area commander, his division was the one one conveniently positioned to cowl Hill’s flank alongside the Charles Metropolis Street within the assault and, given the general simplicity of his plan, Johnston had no motive to anticipate something however success.

Johnston’s report of June 24, 1862, took full benefit of Longstreet’s narrative and instantly conflicted with Smith’s earlier report. Earlier than evaluating Johnston’s report, nevertheless, you will need to flip to Smith’s notes and feedback about what had transpired on Could 31. (Smith entered handwritten feedback on his unique report whereas in Macon, Ga., in June 1865.) On the morning of Could 31, and all through a lot of the day, Smith was with Johnston. They interacted and communicated continuously, and each knew Longstreet had deviated from Johnston’s orders.

The request by Johnston for secrecy perplexed Smith:

“Johnston’s letter indicated a want to maintain again necessary information. And he’s mistaken in supposing that the misunderstanding between himself and Common Longstreet didn’t have an effect on the operations of my division. And he’s mistaken that nobody knew of this…

“Common Johnston didn’t know the place Longstreet was. However he defined his intentions freely & totally to the impact that the precise wing below Longstreet composed of three divisions viz – His personal [Anderson’s], D.H. Hill’s and Huger’s have been to assault the enemy very early within the morning earlier than eight o’clock. D.H. Hill by the Williamsburg Street…Huger on Hill’s proper…and Longstreet’s personal division on Hill’s left shifting into place on the 9 miles street….[All my] employees officers and Generals knew the place Longstreet was imagined to be and so they knew Genl. Johnston’s intentions and orders in regard to the troops they have been to help. I gave them the data and definitely didn’t dream that there was any event for secrecy or ‘reticence’ then, nor do I understand it now.”

Later in Smith’s 1865 endorsement, he addressed the so-called misinterpretation with: “A lot for the misunderstanding between Johnston and Longstreet….My opinion is that it might have been higher for each had Johnston said and defined it.”

What Johnston’s official report had emphasised was that Longstreet’s Division supported Hill’s Division alongside the Williamsburg Street, and that Longstreet had “the route of operations on the precise.” Huger “was to assault in flank the troops who would possibly interact with Hill and Longstreet,” and “Common Smith was to be in place alongside the 9 Mile Street “to be in readiness both to fall on Keyes’ proper flank or cowl Longstreet’s left.”

The one factual assertion right here is that Longstreet possessed command of operations on the precise (though he did little commanding). The opposite statements are all false. “[H]advert Common Huger’s division been in place and prepared for motion…,” Johnston opined, “I’m glad that Keyes’ Corps would have been destroyed reasonably than being merely defeated.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! publication for the most effective of the previous, delivered each Monday and Thursday.

Johnston knew the plan he described in his report will not be the one he outlined to Smith and others on Could 31. Relatively than personally adapting and adjusting to the brand new state of affairs when the plan unraveled, he turned sullen and passive. At 10 a.m., listening to no sounds of musketry or distant cannon fireplace, Johnston requested a employees officer if there could be a mistake—that his ears had deceived him. When the officer confirmed the silence, the dejected Johnston sighed, “I want the troops have been again of their camps.”

Mockingly, it was the success of Jenkins’ Brigade that demonstrated simply how profitable an assault down the 9 Mile Street may have been. Jenkins’ 1,900-men drove throughout a portion of the Federal proper flank close to Honest Oaks Station after which adopted a path down and throughout the 9 Mile Street whereas slicing behind the Federal strains at Seven Pines.

Jenkins’ assault alongside the same path to Longstreet’s, with six brigades, ought to have been launched from Outdated Tavern that morning. Given the success Jenkins demonstrated, one can solely ponder the success Longstreet’s full division may need attained. An earlier assault down the 9 Mile Street would perhaps have convincingly gained the day for Johnston’s military.

Wrote Keyes: “[T]he proper was on floor so favorable to the method of the enemy and so removed from the Chickahominy that if Johnston had attacked there an hour or two sooner than he did, I may have made however a feeble protection…and each man of us would have been killed, captured or pushed into the swamp or river earlier than help may have reached us.

The specifics of Longstreet’s June 7 letter to Johnston remained unknown to Smith, Hill, and others till its publication within the Official Data. Smith and Hill have been equally rattled, with Hill penning in a letter to Smith on Could 18, 1885: “I can not perceive Longstreet’s motive in coming over to the Williamsburg Street, nor can I perceive Johnston’s motive in shielding him.”

Hill and Smith have been incensed at Longstreet’s claims that his division had endured “maybe the toughest a part of the battle” and that it had been “tremendously lower up….[their] ammunition…almost exhausted.”

“Longstreet was not on the sphere in any respect on the thirty first of Could and didn’t see any preventing,” Hill wrote. “He must have identified that I acquired no help from him aside from the brigade of RH Anderson [i.e., Jenkins]….I’ve not felt kindly to Longstreet since I learn that letter of his to Joe Johnston. I can’t perceive how he had the brass to write down such a letter.”

In his Battle of Seven Pines, printed in 1891, Smith expressed his sympathy for Huger, as “the inaccurate statements of Generals Johnston and Longstreet, in regard to Huger’s directions, have been included into historical past.”

“Too A lot Censured”

The one official help Huger acquired instantly after the battle got here in Wilcox’s June 12 report. Wilcox had commanded three of Longstreet’s brigades alongside the Charles Metropolis Street on Could 31 and had been in common contact with Huger. He knew Huger was not at fault for the disruption at Gillies Creek.

An undated addendum in Wilcox’s report, presumably added after Johnston’s report appeared, states: “At Seven Pines, the profitable a part of it was Hill’s battle. I’ve thought that Common Huger was a bit an excessive amount of censured for Seven Pines by the papers.”

Johnston continued the “blame Huger” theme in a post-war article he wrote for Century Journal titled “Manassas to Seven Pines,” as did Longstreet in his 1896 account, “From Manassas to Appomattox.”

Huger didn’t see the essential studies by Longstreet and Johnston about his efficiency till August 1862 and instantly sought redress from each. Longstreet by no means responded, and Huger wrote on to Johnston on September 20 after ready greater than a month for a reply, sustaining: “As you’ve indorsed his inaccurate statements, to my damage, I have to maintain you accountable.”

Receiving no reply from Johnston both, Huger penned a letter to Davis, together with an extract of Johnston’s Seven Pines report, refuting what the commander had written. Davis referred the remarks to Johnston, receiving a supercilious response. He basically blamed Huger for not elevating the difficulty sooner and that an investigation was now unimaginable as a result of Longstreet was unavailable, including that “the passage in my report that he complains about was written to indicate that the delay in commencing the assault on Could 31 was not by my fault.”

Huger tried to proper the flawed by the Accomplice authorities itself—to no avail. He demanded Davis create a board of inquiry, and although the request was permitted, that board by no means met.

Huger dropped the difficulty after the battle. In 1867, he wrote: “[I]f our trigger had been profitable, I’d have insisted on an investigation; I decided that it was now no time to redress wrongs; that I have to proceed to bear them and I’d not point out a phrase about Gen. Johnston.” Thus, Huger’s title and character would proceed to hold the blame for the failure of the Could 31 Accomplice assault at Seven Pines.

Mercifully, by late July 1862, Huger not held a area command, reassigned to the executive position of inspector basic for artillery and ordnance. Johnston, in the meantime, resumed main Accomplice armies in November.

Maybe Gustavus Smith supplied the most effective description as to how historical past ought to view Longstreet’s lack of moral credibility when he wrote: “Common Longstreet, accountable for the three divisions which have been to have crushed Keyes corps earlier than it could possibly be strengthened blundered badly from the start to the top of the battle; and to say the least, his writings in reference to Seven Pines aren’t any extra creditable than his conduct of operations on this area.”

Victor Vignola writes from Middletown, N.Y. This text is customized from his e-book Contrasts in Command: The Battle of Honest Oaks, Could 31–June 1, 1862 (Savas Beatie, 2023).